On Street Etiquette, Black Dandyism, and The Will to Adorn

An interview with Travis Gumbs and Joshua Kissi

Founded in 2008, Street Etiquette—a culture and style blog created by friends Travis Gumbs and Joshua Kissi—ignited a new era of black sartorial expression. With West Indian and West African roots and an upbringing in the Bronx, Travis and Joshua put their diasporic spin on prep, and indirectly, added to the lineage of the Black dandy. It was truly a moment—first in New York City, then globally, as their travels took them to places like Brazil, Germany, and South Africa. And, it arrived at a time when we were redefining the ways we found community—mostly online. (Full confession: During my four years at Howard University, my friends and I, really anyone who cared about style at the time, were tapped in!).

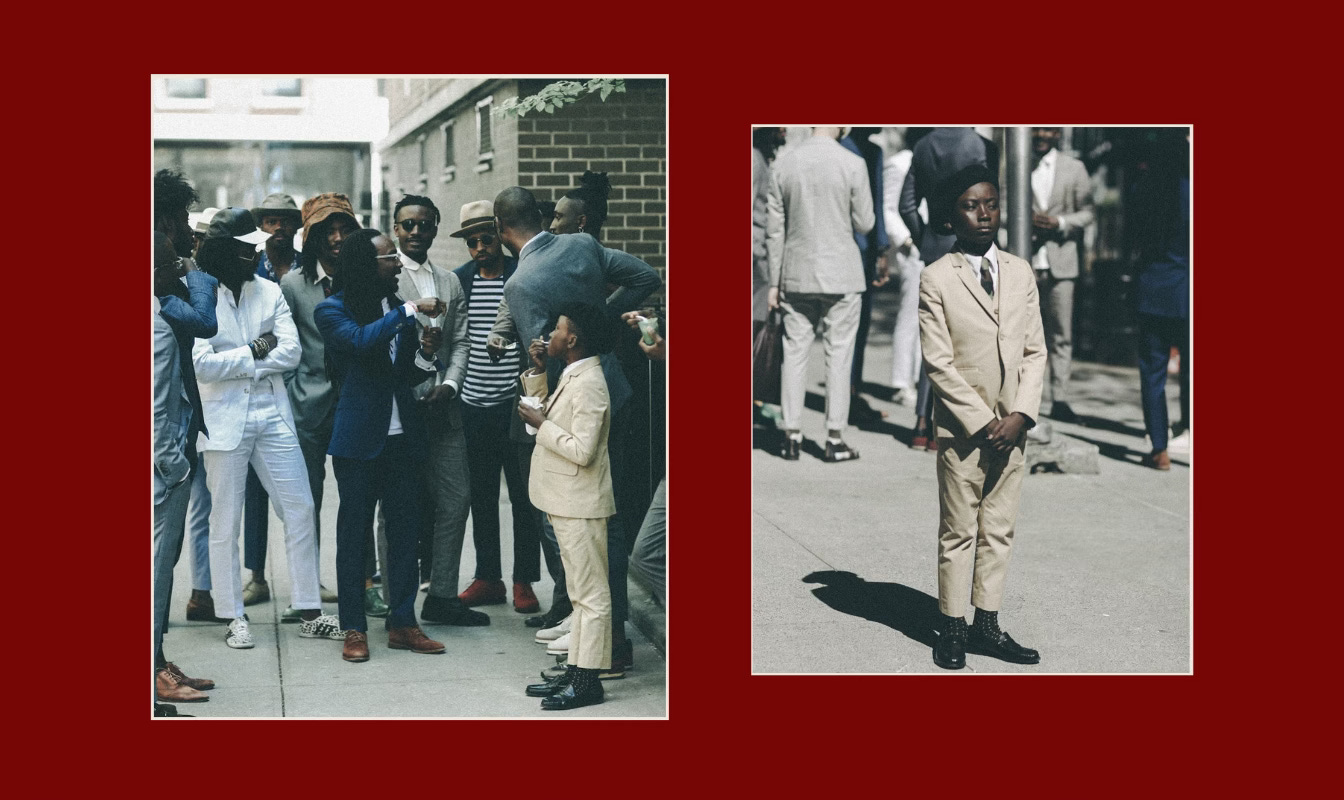

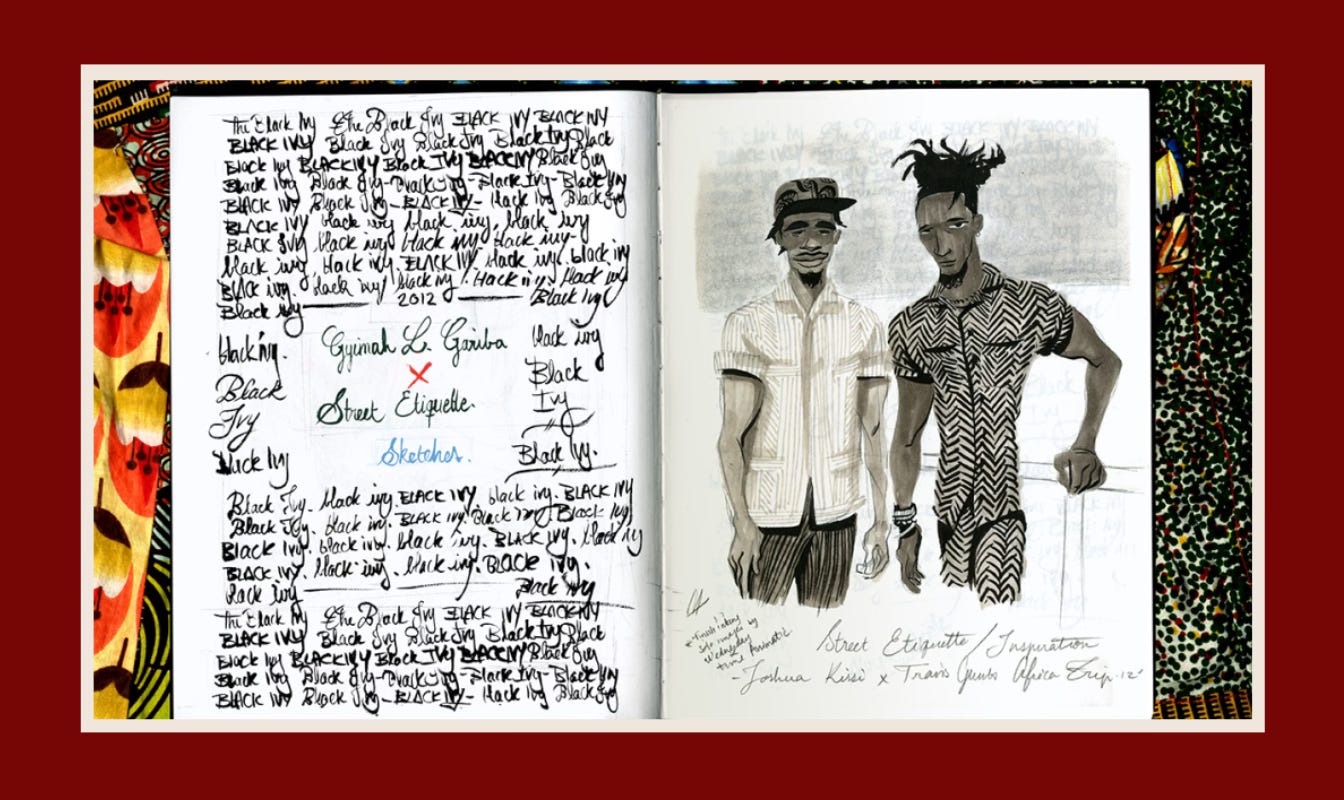

Street Etiquette was more an intellectual project about Black culture and style than a fashion blog. Travis and Gumbs weren’t posting outfit photos—they were using style to tell stories and change narratives. Editorials like Black Ivy, inspired by 50s’ and 60s’ photos of Howard University students, reclaimed scholarly, respectable dress, while Slumflower subverted narratives about the Bronx public housing. They didn’t identify with the term—but this is the core of Black dandyism: using style to subvert narratives and aesthetics to rebel.

It’s why I was so perplexed when I saw that Street Etiquette’s contributions to black dandyism were left out of the most recent conversations publications were having around the Met Gala and the Costume Institute exhibition. (Note: Street Etiquette is include in the book, Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style). So, I reached out to Travis and Joshua to talk about the past, their present, and naturally, one of my favorite essays by Zora Neale Hurston, “Characteristics of Negro Expression”, which informed the structure of the current Met Costume Institute exhibition “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style”.

We talked about rebellion, their West African and West Indian upbringings, tailoring, and the lasting legacy of Street Etiquette.

Editor’s note: This interview goes deep, which means it’s pretty long, so you likely won’t be able to read the whole thing in your inbox. Open in your browser or read on the Substack website or app to dive into the full conversation.

Also, another conversation about black dandyism that I thought was superb and really got into the mindset was this one from Aria Hughes at Complex with June Ambrose, Dapper Dan, and Ali Richmond.

Ridiculous Little Things: Joshua, you have roots in Ghana. Travis, you have roots in St. Kitts. I’d love to know, in addition to growing up in the Bronx, how did your upbringing shape your relationship to style?

Travis Gumbs: Being from St. Kitts, style was always such an embedded thing in the culture, and I feel like for Africans, it’s the same thing. There's something really ancestral about expressing yourself through colors, especially in the islands. And then Sundays—everybody dresses up to go to church. Me, personally, I had to wear uniforms, so your uniform always had to be clean and pressed, even though as a kid sometimes you didn't really like that. But it actually built a certain discipline in of how you want to represent yourself and step outside. Also, just culturally, I was thinking about this the other day because my son really liked a Mexican dancer in costume, and I remembered that I used to love the dancers during Carnival. It just made me think of how Africa also has the same thing. So, it's like there's these things that are linked to culture, linked to dance, but they have such a profound stylistic element that it's otherworldly and how people use that essence when they express themselves with style.

Joshua Kissi: I don't think it's by accident that the Afro-Caribbean interpretation of what we were doing with Street Etiquette connected to a lot of people, even beyond us. But in the moment, it just felt like we're from the Bronx, we're doing our thing. We would add cultural touches to it. But now, zooming out and looking back, I'm like, there was a lineage and we just fell in line without even knowing. That color, that extra, that whatever it was that made us gravitate towards how to express ourselves stylistically, I felt like it was something that was already embedded. It's like, damn, you have two kids, one from the West Indies and one from West Africa, and we’re interpreting what New York and being American means. Like, we would wear Clarks because we saw everybody in the Caribbean wearing Clarks and desert boots, and it's like we were always harkening back, going back there, even with the way we wore our hair, the way we played with the textures. But even thinking culturally as a kid—seeing the uncles and the aunties come with their Kente and their fabric—and at first, it was like, I didn't want to wear it, you gotta show half your chest and wear it. It was just like, “Yo, there's no swag to this”. But I started to understand that even how the Kente falls is its own thing; you got to know how to wear it, hold it, and walk around and still hold this level of prestige. So as I got older, I started to appreciate it. But when I was younger, I'm like, “Yo, I'm not trying to wear all this blanket”. I think it was just in conflict with myself as being American, but still carrying the culture.

RLT: I really liked what you said about the Kente cloth—it’s not just about how it’s tailored, but also about how you carry yourself. That plays into the idea of Black dandyism as a performance and mindset, not just getting dressed. Are there any specific people who come to mind when you think about Black Dandyism?

JK: We loved Miles Davis, Langston Hughes, even Bob Marley; the inspirations were just all over. It wasn't just about wearing a suit and going outside, but it's just with the clothes that you were wearing and how did that represent the space you were in. Even though I know people wouldn't think of Bob Marley as a traditional dandy per se, but there was just a prestige to how he showed up in conjunction with Miles Davis and Langston Hughes and other people during that time.

TG: Bob Marley was definitely a dandy man. I've been thinking about dandyism just because everybody's been talking about it. But coming from someone who is West African and someone who is West Indian, our interpretation of dandyism really came from those roots. So for me personally, I thought Bob Marley was one of the greatest representations of dandyism, because dandyism is almost like a mentality. It's a rebel mentality. You have style with it, you know what I mean? But, you are using the style to display how much of a rebel you are.

RLT: I think the way people are thinking about dandyism, especially in regards to white mainstream magazines, is only about being polished, but it's really about subversion too. It can look a lot of different ways because it's about being rebellious.

TG: It’s about being rebellious and fly at the same time. Right now, a lot of the conversation is only reflecting on being very buttoned up and very dandy in that traditional way, but I'm like, there's so much variation to how you show up. When I think about our friends Sam and Shaka from Art Comes First—-yeah, there's elements that are dandy, but there's some elements that are punk and rebellious. I don't think there was this one image that we saw and we were like, it needs to be that.

With style in general, we know that every decade is different, but every decade also does produce people who have that same mentality. So again, Bob Marley was in the seventies, so you had more of a hippie vibe, whereas if you're talking about Miles in the sixties, it's more sartorial, thin lapels and more buttoned up just because at that time, seeing a black man dress like that, that was an act of defiance. And, so you’ve got to look at every decade and say, who were those rebels who showed up. Dandyism comes from the trenches, these whimsical figures within the community, it was never a celebrity. I mean, they're local celebrities. A$AP Rocky, I definitely admire him sartorially, he has great style, but back in the day he was on a whole different tip and now he's the representation of a black dandy. I'm not saying that it's supposed to be us, I'm just saying that community wise, that's more of an anthropological study. I feel like today because of social media everything has gotten so celebrity focused that whoever's the new black face of the moment, you put him in a suit and then ask him about what black dandyism is. The only person really speaking to it at length, who really seems to understand it, is Dapper Dan. The only one speaking to the mindset.

JK: At the same time, we can't hold both to try to solve for all the things because they're not equipped to, so that’s why you need those intercultural voices and storytellers.

RLT: I’m also thinking about the era you came up in. Hip-hop had a huge influence on how Black masculinity was expressed, and perceived, especially through style. How did that atmosphere shape or challenge the way you thought about your own masculinity?

TG: Street Etiquette was at the tail end of the gangster rap era, with a very hyper-masculine style and mentality. This is partly what inspired Street Etiquette to begin with. We felt like there was space to expand the expression of what it meant to be masculine and how we could express that stylistically. It was actually really inspiring, because immediately after we started Street Etiquette, we began meeting other people from different boroughs who were into the same thing, and it sort of created a community. So, although we were pushing boundaries within our own communities—which did take courage on our part—we also had our own community of people who were inspiring us to explore even deeper.

RLT: How did you first learn about the term dandy? When you launched Street Etiquette in 2008 was that term in mind?

TG: We didn’t like that term at the time. For the same reasons that we're talking about, at the time, I felt like the dandies were more so the Fonzworth Bentleys and we felt like we were coming with a little more grittiness, even though it was super buttoned-up. We felt like we're coming from a concrete jungle perspective. It's not necessarily dandyism, twirling around an umbrella.

JK: It was like how do you put on clothes and communicate a message rather than, okay, we started it with this idea. I think people attached that to it after, but we did so many different creative works and editorials that spoke to different levels of style, but they all had their own sort of details.

TG: But looking back, like I said, I feel like every decade there are people that, whatever you want to call it—so I feel like if we're using dandyism to explain a certain subset of people who show up with style—-you can build on the list and every decade find people. I feel like we definitely took a lot of that energy and were those people for that time, but I mean that's just a term. So it's almost like what does the term really mean? Because for us back then, it was like it had a certain terminology with it that we didn't feel like we fit in perfectly.

RLT: You talked about being rebellious with Street Etiquette, in what ways would you say you felt like you were rebels in your community at that time?

JK: For us, it was like we're mixing elements of street and the contrast of coming from the Bronx and this level of rebellion, but still with a level of refinement. That's what Street Etiquette is in general. Back in 2010, there weren't that many people in our age demographic dressing that way, so we stood out. And then, you think about the work we did, Black Ivy was one of the editorials that leaned more into prep. Prep was the sort of the idea and aesthetic that we were classed under, and the Black Ivy editorials, if you look at it as an album, that's probably the well-known single. That was one of the first things that I think went viral within the culture online. Prep was the thing, and Black Ivy was the thing, but those images were inspired by images we saw from Howard University in the Life archives from the 1950s and60s. So it's like we were still giving this nod to the past, but then we were mixing it in with different elements of wearing sneakers instead, maybe there's no tie, maybe there's no bow tie. Maybe you add a sweater underneath, maybe you wear a t-shirt, maybe the jewelry you wore was different, maybe the haircut we had was different. Everybody was trying to find their own ways of “Where can I rebel?” or “Where can I express myself?” rather than what makes sense on paper. We had friends who called us “prep bandaids”.

TG: It's so hard to explain now, because it was such a different time. But, back then, we didn't have that many representations of different styles all at once from different people in one classroom. It was kind of more homogenous. It was like we were coming off of the era where everybody was wearing everything baggy. And, we went to a really hood school, it wasn't like we were in prep school or anything, we were in the trenches. Then the times were changing—once we started it up in 2008, Obama became president, so at that time it was a different sentiment, being like, “Maybe I could step out of the box.” Obviously, you had people like Andre 3000 and Kanye paving the way for people to feel like they could try out different things. But, what did we do that made us feel like we were a rebel? It's so hard to describe that now because the dude in the hood is wearing a clutch purse, so it's like you’re not going to understand how aggressive it was for us to do that and then not back down in the face of everybody looking at us like we're crazy.

JK: That's so real, now it's so different. It's almost like your mindset needs to be on another level now.

TG: I know about the Civil Rights movement, but I never really got into it on a deep intellectual level. Recently, I've been reading a lot about what happened during the era, and I picked up Harry Belafonte's autobiography—I didn't even think I would be into it—but it was phenomenal. He played a pivotal part during that exact time helping those exact students [from the Howard University Life Magazine photos]. Then that led me to read Kwame Toure’s biography, who was literally one of the dudes in those photos. It's so interesting to see their mindset because their mindset is literally the mindset that we had; Walk by ourselves, self-respect, and we want to show up in a world that wants to keep us down, but we have to rise above it. You know what I mean? Even in our own communities, we have to show up in a different way, even if that means we are going to get backlash. That was totally what our mindset was at that time. But it's just interesting how things could resonate with you even if you don't really know what the full story is.

RLT: And even then—going back to that idea of rebellion—during the Civil Rights Movement, dressing in their Sunday best was a form of resistance. It challenged stereotypes and created a powerful contrast against the violence they were met with.

TG: I think it was also that level of pride. That's what we saw in those photos. We saw a pride and expressiveness that we were like, “Damn, they got swag”, even if they look very different from us. It’s the pride that they were walking around with that made us feel confident to be able to do the same in our own interpretation.

RLT: What were some of the first reactions you got with Street Etiquette and the way you were dressing?

JK: It depends on who you ask. Of course, the older people enjoyed seeing us. But most times, for our peers, you either have a curiosity where you're like, “Oh man, I want to try that, and I love that somebody else is.” Then there's also a group of people who felt like it was insulting for us to dress that way and also be of a similar age. It's unfortunate, but a lot of the smoke we got was from people who looked exactly like us and were the same age—which is its own thing.

RLT: I’d love to talk about your relationship with tailoring. Was that something that you grew up with or something that you got more into once you started Street Etiquette?

JK: I feel like tailoring is just a part of the household. Being African, being West Indian, I feel like your mom is always going to have a sewing machine in the back, even if she doesn't use it—somebody's using that sewing machine. And I don't know, even the grandmas and the aunties, someone always knew how to patch up things, fix things. I grew up seeing that Danish cookie tin can with all the sewing tools. But, we started to appreciate tailoring more when we’d go into these different tailor shops. This one at LES, Stanton Tailor Shop, we have a really good relationship with the tailor, Pablo. He became big when we put him on our blog and a lot of people started going to him at the time. He was a big element in our relationship with understanding tailoring, especially once we were really into vintage and thrifting. But also, at all these Ghanaian and Nigerian events, you needed to have a good tailor. Even with my mom, she had a beauty supply shop and she had a tailor that's there as well who made custom fits for people. So I grew up around it, but I feel like it wasn't until I was like, “Oh, we could have a one-to-one relationship with the tailor and tell him what we needed based on our vision.”

RLT: I feel like my grandma always says “looking sharp”. At the time, what did looking fly or sharp mean to you at the time and how has that evolved?

TG: I don't know if anyone who's really into style has ever felt like, “I'm at my peak, I’m going to stay like this”, there's always a shift in tide. Like, now I want to put on a suit or now I just want to wear jeans and a nice shirt. It's always something that's shifting, so it's hard to say exactly what about my style that I've kept, it's an evolving thing. It's a feeling sometimes. Sometimes you're not vibing, sometimes you're not in a goodspot. You're like, “Man, I need to feel summertime here and you're like, wait, this just woke up a whole new level—now, I’ve got 10 options I need to try.” It's all about the vibe that you're in at the moment. But for me, there's a prep part to my style that is just who I am. It's hard to know when you're younger because back then we were trying just everything man. But, with time you figured that out because you can see the consistency. There's an element of a prep that's always there, even when I'm dressed, even when I'm wearing sweatpants, sometimes I like to throw on a button-down shirt.

JK: I've been inspired by Trav living in Mexico. I've seen what that being there has done for him sartorially. It’s been dope to see the texture, the gator, the skin. Just like in New York, there’s a certain way, but now seeing Trav in Mexico City, it's almost this different spiritual connection to the land that manifests clothing wise too. So, whether it's a leather hat or snake skin boots or whatever, it's dope to see the evolution of prep in that way. I was going to Ghana a lot, so I was wearing all the bold stripes and colors. Whatever season in life that you're in and where you’re frequenting most starts to rub off on you. I feel like five years being in LA, there's more of a relaxed vibe to things, but there's still a prep vibe to it too. I would see these skater kids in Compton, I'm like,”Yo, these kids really got khakis on with penny loafers and a button-up shirt, but he's in the hood, and he's got his red LA hat on, still affiliated.” It is very interesting to see that, and it inspires me.

When we're in New York, there's a certain type of—we're going to be walking from here to there, where I got I need to be lit, but we're taking the subway; it's almost like you put on a fit that you have to survive the whole day with, the whole city gotta see this fit. Now it's just different because you're in a car half the time, or you're in nature. All of that's to say what Travis was saying: I don't think you're just hitting this peak, but it's like you just find the grooves. Obviously, now we're both parents, so we want ease, we want comfort.

TG: The pants can't be so tight these days. And then we don't got enough time to really be in the mirror, really examining. Throw on what works, and it's like this might get some food on it, this might get dirty. But it's like a sense of ease is important too. So the season of our life is so different than just caring about ourselves, now we got families, we got wives, we got kids. It's a whole different thing.

RLT: On the Street Etiquette blog, you were also sharing music and other cultural things that just really showed the expansion of your taste and interests. How were you discovering all these things?

JK: It was online culture plus this global sound. When we would travel to Germany or go to London or go to South Africa, it was like we just started to really be like the sounds out here is different. Traveling around the world helped us understand that there’s a global sound and evolution happening—sometimes bigger than what was happening in hip hop. For us, every editorial had a sound to it because with music, you show up a certain way, they come dressed a certain way. For us, it was a mixture. We never really—during the height of Street Etiquette—we never really had a sound from somebody commercially that represented us, maybe Theophilus London or Yasiin Bey, though he was at a different point in his career then. But I think in terms of newness: Theophilus London felt like there was a sound and a look; whether he was wearing Starter caps with Jordans and penny loafers, or a Starter cap and a vintage shirt. We started to all kind of blend in that era where we were really into vintage—we were still into prep—but we were mixing.

RLT: In Zora Neale Hurston’s essay “The Charateristics of Negro Expression,” she says “The will to adorn is the second most notable characteristic in negro expression.” How would you guys say black people’s, especially black men’s, desire to adorn themselves has been historically dismissed as just excess or vanity?

TG: You can look at black people all over the world and there's just a certain essence that we carry. And then certain music and certain cultural points that are all connected, and style is one of them. I definitely feel like if you go back, like I said earlier, you go back to ceremonial garb, it's all really colorful, really intricate. It's almost like dressing as this literal peacock, you're dressing like a bird. All of the different African cultures and everything that's spawned from that, being in the West Indies and Latin America—it carries that spirit. So when you look at it in a modern sense, you can look at it like, “Oh, Black people are materialistic and all this stuff”, but you're negating what ancestry says. We love to get fly, that's just part of our DNA.

RLT: Last year, I read this book called Dress Codes and another book called Creole, and they both show examples, essentially of Black people’s flyness and self-expression, causing so much fervor for white people that they created laws around what they could wear or would take their clothing, anything to try to take away their dignity and keep social order. But, it’s so funny, because even within those confines Black people were still able to defy and be fly. There’s an example of there being a law against Black women wearing their hair out, and even with being made to cover it with scarves—it was still stylish.

TG: It's a real part of our culture that we all hold onto it, some more than others because we're all different. But there's a part of our culture that has that in it. So it's like no matter what happens— and, it's almost how you deal with the world also, you get dressed in a way that you want to feel and it helps you feel that way. I actually think black people in general are very emotional people, our bodies are very emotional and very physical, and that's just another way that it shows up.

JK: We're always storytelling, whether it's through our clothes, our music, our hair—even to the story you were telling about them telling black women to cover up their hair and the fact that the scarves were still fly. It’s like you can't block us. How we show up is how we show up.

RLT: Do you think that clothing allows you to say something about yourself that maybe language doesn’t?

TG: Definitely, I feel like when me and Josh met and gravitated towards each other, style was definitely at the forefront of that. We weren't necessarily dressing prep at that time. We were more into streetwear, but there was just this element of, “Oh, you trying to do things a little bit different than how everybody else is doing it.” I feel like in general, in your day to day, the type of people you gravitate towards have a similar way of showing up, especially when you're younger or whatnot. You can go somewhere and you understand, “Oh,this crowd is X, Y, Z.”; there's some little cool nuance going on that those that know are going to know and those are the type of people that I vibrate with anyway.

JK: Now because information is so available, it's knowing the right information that creates the distinction. You can find information anywhere, especially online, but it's like if you know the right person, the right tailor, the right whatever it is, you find your tribe. Now that people have so many choices, it's like it's a matter of taste and nuance and sometimes it goes over people's heads, but that's a good indicator of, “Okay, we may not connect because they're not even seeing that part of this conversation.”

With style and fashion, you're almost having a conversation with only those that understand it. I think we were already familiar with that growing up in New York City and then coming from West Indian and West African households. You already understand how when you get home you can speak a certain way or your mom can speak a certain way, just a change of tone and attitude, which will change the message that they're trying to tell you. We understood that in a way with our stylistic choices. So for me, clothing was always a layer of expression of language to the world, but then within that expression, there's some people who understand it more deeply. It's almost like broken English. I don't know much about linguistics, but there's almost like a patois or pigeon to how we look at style.There's elements of English in it, of course, because of all the influence, but then you break it down into your own cultural dialect to make it make sense.

RLT: That was actually on par with my next question. In the same essay, Zora Neale Hurston talks about when adorning themselves black people aren’t imitating whiteness, they're transforming it into something of their own. Were you thinking about this during Street Etiquette—or, did people every say these things to you directly?

TG: Definitely. There were definitely people saying, “Oh, you're trying to dress white and all this stuff,” but I mean, again, that wasn't the case—we were referencing photos of actual black people. But, I mean, we knew it and understood that part though, so it wasn't like we were conflicted. We were actually celebrating our people and how we can add new flavor to ourselves culturally. So, we never really battled with that part of it. We were so proud to be black.

JK: And, on top of that, we weren't really in environments like that. Most of our environments were pretty black. Not until we started going downtown that we were in different environments, but even then, we still wore that flag in pride. That's why I think those images at Howard University connected to us. No matter where we go, whatever room you go in, there's a sense of history and a sense of self and I think we've carried that without even knowing. We're just like, “This is just who we're”, there's no need to justify it, it just is.

RLT: How do you see Street Etiquette's legacy fitting into the broader archive of black expression and black dandyism?

TG: Even now, there are people—here in Mexico,too—who are like “I used to read Street Etiquette all the time.” It's something that was so long ago, but yet had such a resonance at that particular time. We're not included in all the Met Gala and black dandyism conversations, but I actually don't feel any type of way about it because we did resonate with the culture at the time and people remember it. One could only be so happy to be able to do something like that in your lifetime. It did the job that it needed to do and we literally left a part of that within everybody else that gravitated towards it. There's no website to visit or anything, so it is literally just a memory that keeps living on.

JK: It's like an album that you really enjoyed that you can't go and play back, but you have it in your head. People were just left with the memory itself, they're left with the impact—the emotional part of it. We showed up at a time when people were looking for something and maybe they didn’t even know they needed it. So to Trav’s point as well, I don't feel any type of way about being excluded. If we continued to do it to this day, that's a different question. But that decade, we really were able to carve out a space for people to feel seen and feel heard. It's like, what else could you really ask for? People work their whole lives to have something that feels like that one time just to someone.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

St. Kitts stan up! 🫶🏾🇰🇳🫶🏾🇰🇳