“I thought she was at least thirty. Because of her ‘eye’ – the real knowledge, taste.”

– Truman Capote, Answered Prayers

Before I even knew the term to describe it, I was infatuated more with the philosophies and sensibilities behind personal style than with the clothes themselves — what we call taste. Now in my 30s, I’ve become more acquainted with my own aesthetic sensibilities and, as a result, started examining the root of my desires. It got me thinking about taste and the term’s origins; about how rooted they are in classism, racism, and spurious posturing.

The recent popularity of “quiet luxury”, “old money”, and “stealth wealth” aesthetics perfectly exhibit the hold that the Eurocentric sensibilities have on our aspirations and our lack of interest in cultivating selfhood.

Often, I’ve noticed that when someone mentions “having taste” there’s an inherent idea of who and what they are talking about: traditional, old-moneyed, the right schools and social clubs, and, of course, white. Which means that even if you have the capital or you can find the dupe, if you aren’t from a certain background, that idea of taste will remain unattainable. It has tainted everything we consume monetarily, socially and culturally: the artists and authors we are told are classic, the attire we’re told is appropriate, the manners we’re taught to have — bringing into question whether you really like it or it’s just what you’ve been told you’re supposed to like to appear cultured, wealthy, and fit into a certain social class.

Indeed, it’s been said that money can’t buy taste, but it seems our obsession with mundane wealth and status signifiers has contaminated our desire to look like ourselves. So, what does taste look like without an attachment to class and capital or in spite of it? What does it look like outside the lens of whiteness? Can it exist?

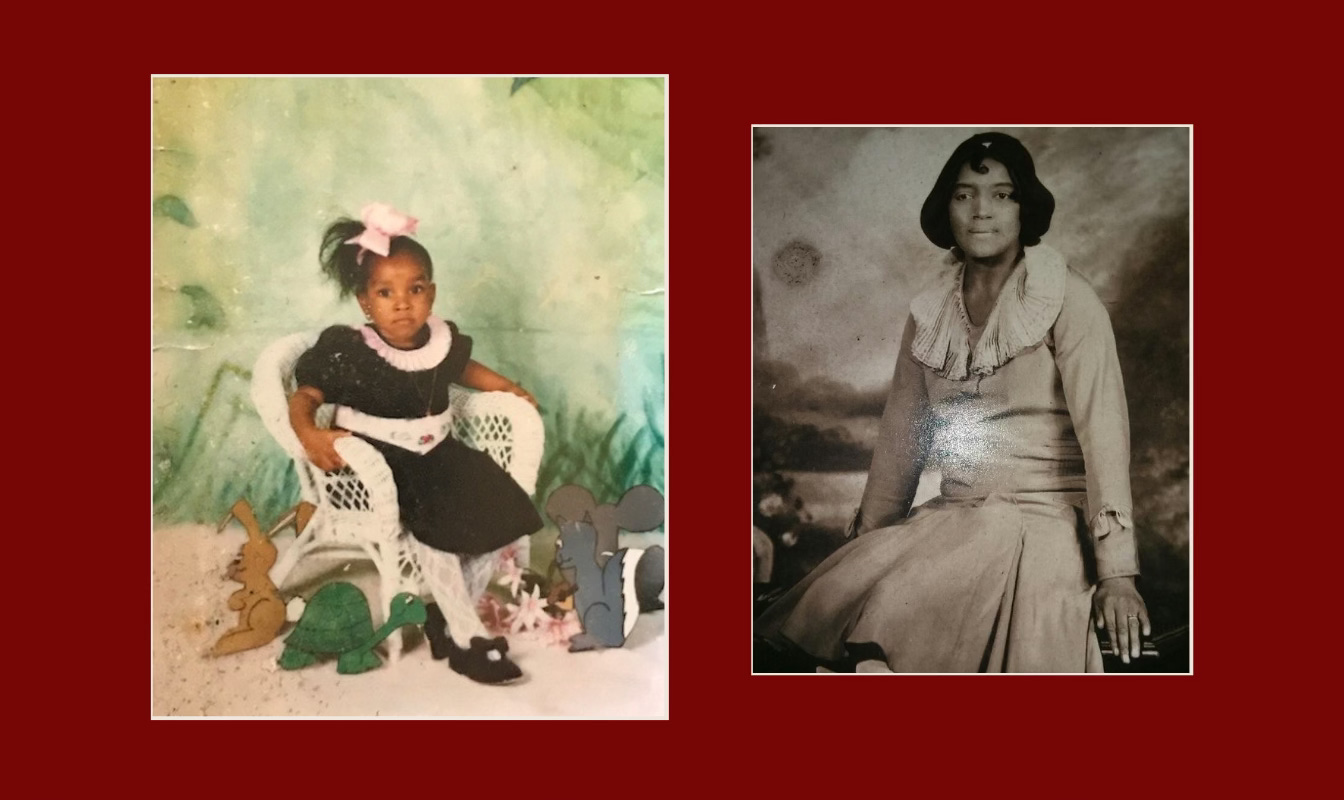

Growing up in the predominantly Black city of Detroit, I witnessed and learned about the various ways that Black people subvert through aesthetics.

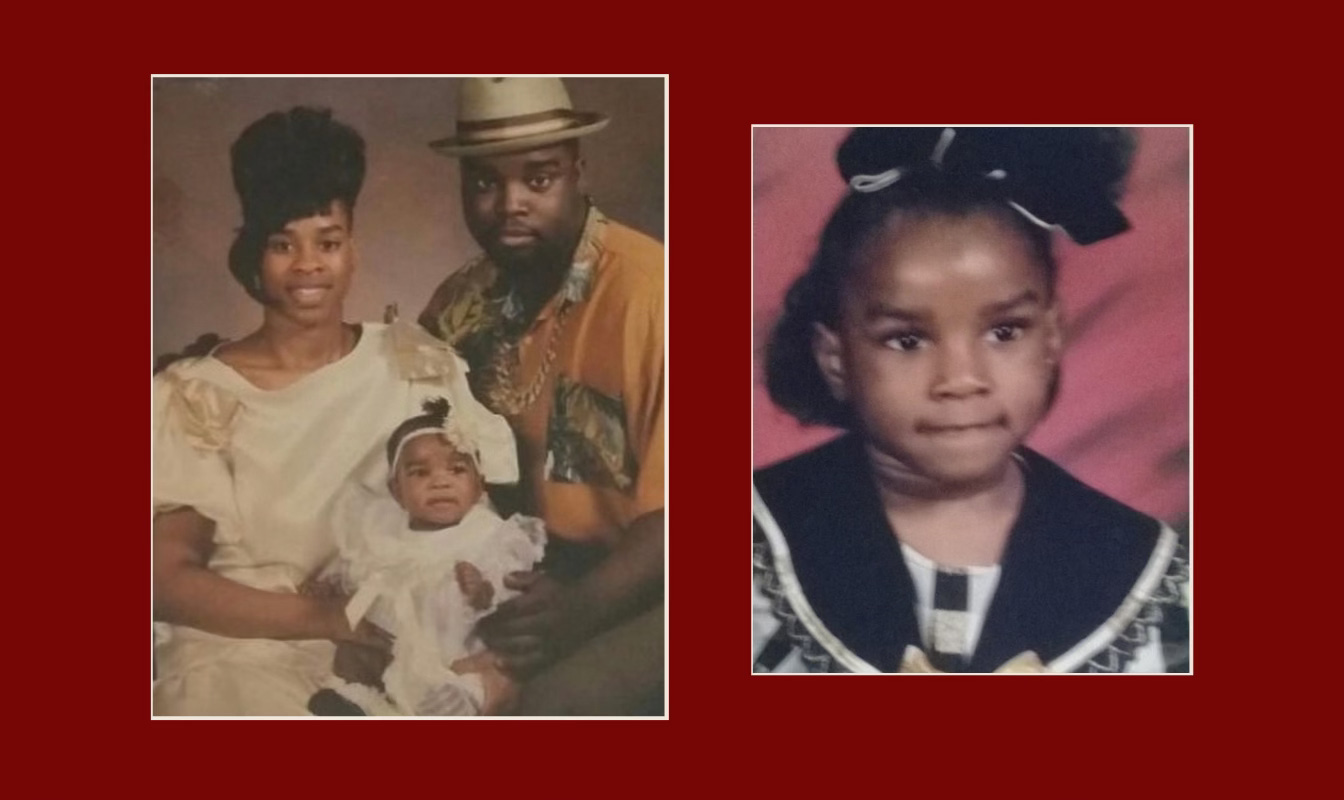

There were Black people who subverted through eccentricity, using ostentatious aesthetics and inventing their own nomenclature and takes on the English language as tools for creating their own world. (LaKeia and Shaniqua are the names of two of my cousins.) Their originality functions as an antidote to the conservative taste of both the Black and white bourgeoisie. They started their own fashion labels and trends and they created their own idea of coveted luxury items: cars with designer logo’d interiors, extravagantly long nails, and intricate, original hairdos. They appeared authentically themselves, taking up space and defying what was “appropriate” in favor of satisfying their unyielding imagination. I always go back to Danyel Smith’s New Yorker piece that describes this fantastical mindset precisely: “When you're ghetto-fabulous, you're buying your way up and out — even if, mentally or physically, you still live there… Never quite tacky, ghetto-fabulous is loud and wrong. It's sophisticated and complicated.”

My father, a drug dealer, General Motors assembly line worker, and a member of a Detroit rap group called Street Lordz, taught me about dressing for myself. He was always the best dressed with a preference for Lou Myles suits, alligator loafers, Coogi sweaters, and Cartier gold-rimmed frames. His love language was material, exposing me to designer brands and to the importance of building a relationship with your salesperson. A tall, dark-skinned, big-bodied man, my father commanded attention, and time spent with him usually involved being seen. We’d shop at the Gucci store (where, at one point, he was dating one of the saleswomen) or Neiman Marcus or Saks, despite skeptical onlookers, and he’d spend thousands of dollars both because he had an affinity for nice things and something to prove.

I vividly remember the black-and-silver velour Sean Jean tracksuit he bought me. I told him I couldn’t wear it, that it was too baggy and for boys. He told me I could wear anything I wanted and to trust him, this would look fly. (The response from my classmates proved him right). At the time, I was about 13 years old; I didn’t understand the impact mere shopping trips with my father had on my sense of self. But seeing my dad flaunt his style and, to my knowledge, not care what anyone thought about it informed my confidence. Overhearing my Uncle Skeet and Uncle Sean recounting the outfits he wore to weddings or to the club were moments that made me think he was so cool. It was my first understanding of what it meant to shamelessly revel in standing out.

Then there were Black people who subverted through imitation, using “respectable” appearance, aesthetics, and “well-mannered” behavior as tools for renouncing racist stereotypes. They created their own social clubs, hosted their own debutante balls, established their own rubric of prestigious universities, etiquette rules, and must-know cultural arbiters. Always appearing polished and well-dressed, in ways that their white counterparts could identify, they ensured there would be no mistake about their status, class, or place in the world. The respectability tactic was used by activists during the Civil Rights Movement as well as members of the Black bourgeoisie, and is still very engrained in Black society today.

I was 15 years old when I attended my first ball, and like most things that expanded my horizons despite my protests, it was a consequence of my mother’s doing. My mother, who had me when she was 19 and was in nursing school at the time, wasn’t upper middle class nor was she considered a part of the Black elite, but she always wanted to introduce me to things that she thought would shape my point of view. One morning, earlier that year, she woke me up and told me to get dressed in my best for a meet-and-greet for CoEttes, a social club for Black girls in high school, mostly from elite families in Detroit, founded in 1941 by Mary-Agnes Miller Davis. The club’s credo was focused on scholarship and philanthropy, but its allure was the social events: tea parties, operas, luncheons, art museum visits, and its annual charity ball paired with ballroom dancing classes every Sunday leading up to the big event.

CoEttes exposed me to the world of the Black bourgeoisie; their mansions with guest houses attached, their professions (car dealership owners, Congressmen, megachurch pastors, CEOs and CMOs, private practice owners), their Bentleys, their art collections, their housekeepers and their inclination to appear upstanding. It was a cultural shock to go from my father’s side of the family, flamboyantly themselves, to intertwining with a community who seemed to care more about what everybody thought and had. While many of the things they did mirrored the customs of elite white people, the root of it, at least consciously, wasn’t “trying to be white,” as Zora Neale Hurston writes in her essay, “Characteristics of Negro Expression”: “The contention that the Negro imitates from a feeling of inferiority is incorrect. He mimics for the love of it.” They had their own flare.

Detroit is a city like no other, especially when it comes to the ways that people prioritize their appearance; the way men wear suits, the pioneering hairstyles of women, and the infatuation with fur coats at every main event, from funerals to Pistons games. As my grandmother would say: “Everyone in Detroit is dressed”. The duality of my upbringing was the foundation for my understanding of the many realms of taste. As I got older and acquainted with how singular the idea was outside of the bubble of my hometown, it helped me understand the importance of aesthetics as armor to navigate and defy the constraints put on marginalized people. Appearance, both in fitting in and standing out, is essential to shifting narratives around taste and cementing identity.

But subscribing to any of the structures built on exclusion reveals that the system is flawed. Yes, Black people use appearance to subvert, but it’s been the same thing that’s helped push the narratives around classism within the community. Again, it’s not that everybody wants to be white, but everybody wants to be classed, and that means distancing yourself from the things that don’t fit into the mold of upward mobility, which was ironically created by white people.

Oftentimes, respectable Black people look down on those who prefer to express their eccentricity: they are too loud, too bold, too ghetto, no class. I’ll always remember my grandmother looking down on other family members who didn’t see the importance of “making something of themselves,” which, to her, meant “talking proper,” obtaining the right cultural knowledge, keeping up appearances and dressing as she considered to be presentable. Even now, when I asked my mom why she thought it was important for me to join CoEttes, she said: “I was in an era of trying to be bougie and I wanted you to see people who looked like you with status.” In many ways, I conformed. It was as a CoEtte that my desires began to be informed by what other people had. I became embarrassed by the size of my home, my family background, I learned immediately what it was to put on a facade and I wanted more and more, not to satisfy my curiosities but to keep up with everybody else.

So while subversion is an important counter-narrative to complicating and reframing our idea of taste and who has it, wealth and class aspirations will always be crutches in the way of pushing the boundaries of what we truly like and desire. In the end, it’ll always show the limits of ambition as the way to attain self-satisfaction and approval. It’s why rich people often have the worst taste: many are only interested in acquiring, excluding, and maintaining their social status above all else.

Consider the ideas of inconspicuous and conspicuous consumption. At a time, old moneyed white people were so enthralled with conspicuous consumption as a display of status that they created rules around what “common people” could wear and buy. For example, the sumptuary laws during the Middle Ages and Renaissance era in Europe, which only allowed people with a certain amount of wealth to display overt luxury. Or, the Negro Acts during the 1700s in South Carolina, which punished well-dressed Black people, claiming they were a threat to social order. So, if a Black person — free or enslaved — was extravagantly dressed, white people could literally take the clothing off of their backs. Now, no longer able to enforce laws around who could wear and flaunt nice things, white elites have deemed conspicuous consumption and crass aesthetics as tacky and tasteless because of who has attained access: Black people, brown people, queer people, people who don’t fit into the mold of their established rubric. In comes inconspicuous consumption, which isn’t inconspicuous to those who can read the signals. It does not mean that wealthy people are now trying to downplay their wealth — they are just playing a different game.

It reminds me of a point a friend made when we were talking about this topic. He said that: “Most people aren’t as historically conscious and for them things exist in a vacuum, but often there is a reasoning behind most things, the main reason being racism and people trying to figure out a way to distance themselves from people of color.”

Which is why it’s important to examine the why in our preferences and not just succumb to our unchecked desires and beliefs around class and wealth. If not, we’ll just continue into the void of cosplaying “having taste” based on a rubric of outdated ideals, Tiktok micro-trends, and spending money. Approaching taste as something you can buy into or project negates what I think it really means to have it: curiosity about the world around you, an eye and desire for beauty and congruence, and an interest in cultivating your personhood as you present yourself to the world.

Of course, we are humans with a sense of belonging, so we are always going to be signaling something about who we are in hopes of attracting the appreciation and acceptance from those we want to be in community with. But, many people don’t have taste because they are more interested in getting it right, which results in copying and pasting an aesthetic, than in taking the risk of being themselves.

So, how can our desires be rooted in something more profound — with an interest to cultivate instead of to project? How can we cultivate taste?

I can only speak for myself. For me, it took examining my conditioning and embracing my upbringing. Questioning why I liked or disliked things, and learning to trust my point of view. Mostly, cultivating my taste has meant honoring a commitment to remain curious about the world, to indulge my desire to learn as much as I can about something that piques my attention, to be unafraid to change my mind. It’s a constant pursuit, with ebbs and flows as I grow and change. I was having a conversation with my friend Karina about the difference between acquiring versus embodying our sensibilities. Issey Miyake had recently died. She was frustrated with comments she’d seen online — people calling others posers for grieving Miyake while not actually owning any of his clothing. “I’ve never cared more about fashion and its history and significance than when I was 16 and broke as fuck, but I could tell you Issey Miyake’s biography and what he was about. That gives my 16 year old self more of a right to mourn his passing than some rich person with a collection of archive designer clothes, who has it just because a stylist chose it for them, and who doesn’t even know or care to know the theory behind pleats.”

Constantly talking to, and getting recommendations from, my friends who have a strong sense of self has continued to push me to think about things that don’t seem like they should matter that much, but in fact do. They are the people I’m most drawn to and inspired why I wanted to launch this newsletter: to have more insightful and thoughtful conversations.

Anyways, this was my long-winded way of saying Welcome to Ridiculous Little Things: A newsletter where I examine our relationships to our desires, talk with people about what informs their taste, talk with authors and artists who have written or made art that relates to the subject, and offer guidance and recommendations around art, fashion, design, and culture that can help expand and develop our taste in a new framework.

As always, I hope to continue abiding by this delicious quote from Zora Neale Hurtson: “Perhaps his idea of ornament does not attempt to meet conventional standards, but it satisfies the soul of its creator.”

Some things I read/watched to help me write this.

Dress Codes A deep dive into the dress codes and laws throughout history that have sought to regulate who could wear what, along with the stories of the people who dared to defy them.

Fashioning Identity: An exploration of the roles of subversion and ambivalence in shaping identity through the lens of fashion.

Ghetto Fabulous: Danyel Smith talks to the late record executive Andre Harrell who breaks down the essence of “ghetto fabulous”.

Theory of the Leisure Class: A critical analysis of the conspicuous consumption (origin of the term) and greed prevalent among the affluent, examining their role in shaping status dynamics.

Characteristics of Negro Expression: Zora Neale Hurston's iconic essay delves into the specificity and originality of Black expression, examining their unique contributions to culture.

Zora Neale Hurston: Claiming a Space: A documentary on Zora Neale Hurston’s life and her contributions to anthropology that forever changed the field.

Our Kind of People: An intensive look inside of the Black upper class in America from their private clubs to HBCUs.

Black Cool: A book of essays that explores and defines the aesthetics of Black cool.

All The Best Possible Taste: A three-part docuseries on the tastes of the upper class, middle class, and working class within Britain.

Class Suicide: The Black Radical Tradition, Radical Scholarship and the Neoliberal Turn: An exploration of Amilcar Cabral’s concept of class suicide and the ways in which members of the “petty bourgeoisie” should be using their positions in the fight for liberations by firstly rejecting their class privileges and aspirations for more wealth and status.

Status and Culture: A deep-dive into taste, culture and why human beings desire status which determines how we live and shapes who we are.

Custom of the Country: Edith Wharton’s satire on materialism, marriage and greed through the iconic, and ultimately dissatisfied, heroine of Undine Spragg.

I devoured each sentence, had to stop eating lunch. Very insightful and honest.

Yes citations!!! Welcome to substack(hell’s playground) I am honored to be invited into your brain space 🌸🫡